Nicholas Day > Writing a simple OpenGL raytracer

2025-12-30

Over winter break, I was reading about NeRF, and got excited to write a ray tracer after reading about the rendering equation. I had followed Ray Tracing in One Weekend before, but this time I wanted to make it faster by using the GPU.

To ray trace a scene, the algorithm shoots rays from the camera origin through each pixel of the screen and check what closest object the ray intersects (sphere, plane, triangle, etc). The ray then either bounces around the scene more until it hits a light to support indirect lighting (reflections, light from other objects, etc), or sends a ray directly to any light source (direct lighting). If that ray intersects another object, that pixel is in shadow. If that ray intersects a light, then the pixel is shaded based on the angle between the surface normal and the light ray. For a more complete treatment on light, check out Bartosz Ciechanowski or Scratch a Pixel.

I chose to use the GPU because there could be a parallel thread for every ray, or potentially every intersection, leading to a theoretical linear speedup with the number of cores. This would speed up how quickly it's possible to iterate tremendously.

A large portion of modern CPUs are dedicated to reducing latency or predicting where branching code will go. GPUs trade off that die space to increase bandwidth and add parallel cores/threads. There is different terminology for each vendor (Intel/AMD/Nvidia). For example, Nvidia's RTX 3090 Ti has 84 Ampere streaming multiprocessors, each of which has 128 compute cores within it. The processing model is single instruction multiple thread (SIMT). Each compute core can be approximated as a single ALU within a larger processor, so there are restrictions on what memory can be accessed easily, and progress in one branch of code can block progress in other branches of code. The best sort of algorithm to run on one "thread" would be a pure function, but broadly it's possible to share data across threads/workgroups (32 threads)/SMs for varying costs with barriers and atomics.

Originally, I wanted to write the GPU code as close to CPU code as possible, so I looked into using OpenCL, but the drivers on my laptop (Linux with Intel UHD Graphics 620 GPU), didn't seem to support OpenCL. Other options included rendering on a server using CUDA, Vulkan, WebGPU, or OpenGL. I didn't want to write 100s of lines of code just to render a triangle in Vulkan. I also didn't want to use something with a big modern toolchain like Rust and WebGPU, so I chose OpenGL to learn a bit more under the hood how it works. OpenGL 4.6 was released in 2017 and seemed to have good support on my laptop.

Project setup

Broadly, I followed Anton's OpenGL 4 Tutorials to get the project libraries set up. For GLFW, I utilized this example which had a crucial definition I needed to get GLAD to work.

#define GLAD_GL_IMPLEMENTATION

#include <glad/gl.h>

#include <GLFW/glfw3.h>To setup GLAD, I used the web configuration and selected the options for header only, gl 4.6, all extensions, and core profile.

For general makefile tips, I recommend this makefile tutorial.

Setting Up OpenGL

The way the threads for compute shaders can be scheduled can be along 1, 2, or 3

axes. I chose to just use 1 axis and use the provided

gl_GlobalInvocationId.x to figure out which "pixel" the current thread is

shooting a ray through.

vec2 pixel = uvec2(gl_GlobalInvocationID.x % uint(image_width), gl_GlobalInvocationID.x / uint(image_width));When referencing older OpenGL code, this blog on how to setup and bind buffers to share between CPU and GPU is a great resource for translating the older code into OpenGL 4.6. Along with docs.gl to quickly search the reference material. It's possible to log out the GL ids that are returned from generating buffers. The GL ids should see integers because OpenGL is managing creating all of the memory in the GPU driver.

I tested if the compute shaders work by writing a simple pure function program that adds 2 buffers together, or adds a constant value to every item in an array. This way it's possible to quickly verify the output, and there is no dependency between memory access among the threads in work groups.

I went with 32 threads in a work group because that's what Nvidia suggests as their minimum. But it may be more accurate to use something like 8 threads on a GPU like my laptop. Intel UHD has 24 "execution units" and 192 "shading units", which I believe corresponds to 8 threads per core approximately. From what I can tell, this number is very GPU and workload dependent, so it may require some experimentation.

There were many errors that I couldn't understand except through trial and error until I learned that binding an error handler is possible. This gist shows how to set it up.

It's also necessary to take the bound storage buffer and render those pixels on the screen. I followed these resources to write a vertex shader that makes a large triangle which covers the whole screen, and a fragment shader to render the colors from the buffer (one, two, three).

Creating Camera Rays

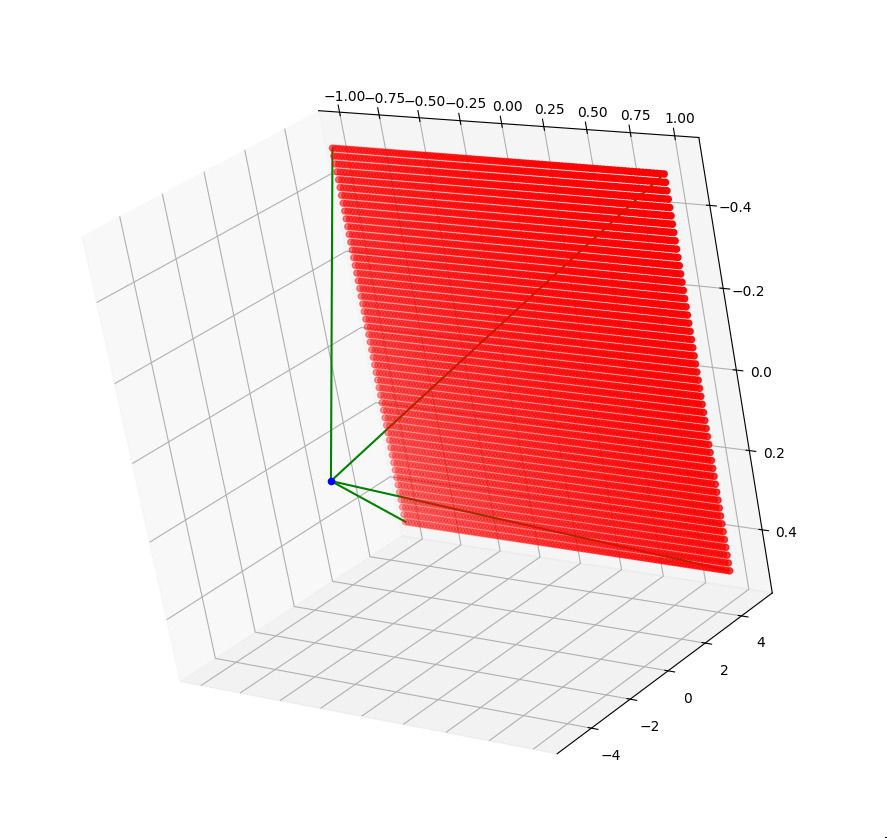

To outline the process, the algorithm makes a camera ray that shoots through a particular pixel given the camera position, the direction it's facing, what is up, the camera focal length, the and the size of the camera sensor. I used just vectors and cross product to find the top left of the camera sensor, then added scaled vectors to get to the correct pixel. This resource details a slightly different approach.

I didn't have all of my OpenGL visualization set up for this, so after working out the math, I wrote the pseudocode in Python and rendered 3d points in matplotlib to check my work.

Drawing Objects

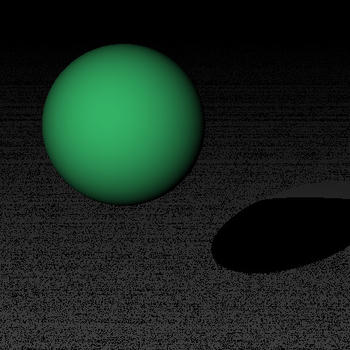

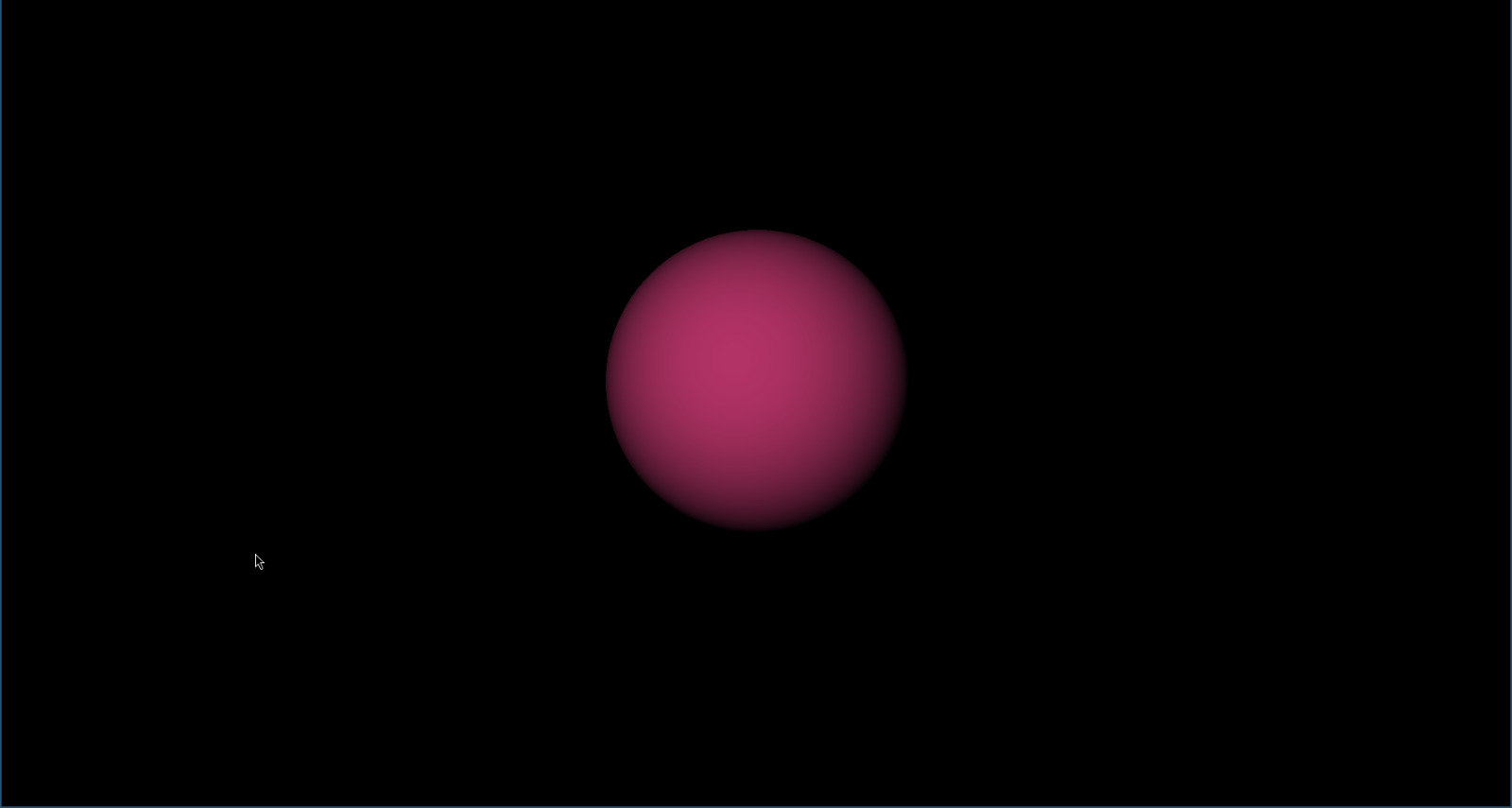

The next task was to see if those infinitely long camera rays hit an object, and if so draw a color. People generally start with a sphere because the intersection is relatively easy to understand. Either a geometric approach or using the quadratic formula works. I chose geometric because it seemed like less square roots, but it's unclear after each is optimized which one is faster.

I guestimated a very simple version of shading by using the angle between the normal of the surface and the vector pointing from the intersection point to the light as an attenuation factor for the color of the object. There are a large number of other shading models like Phong reflection, or Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function

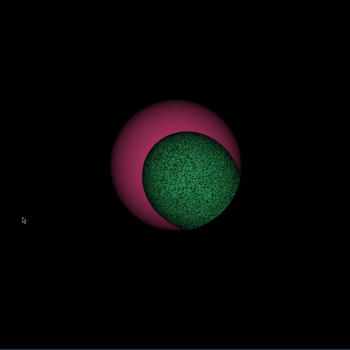

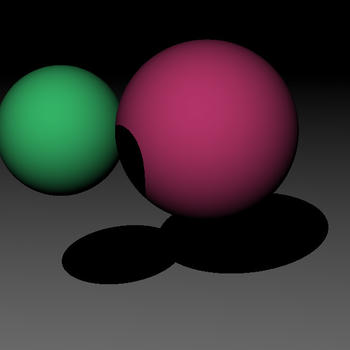

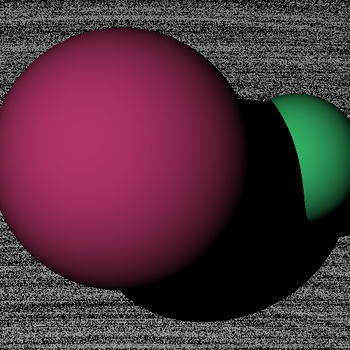

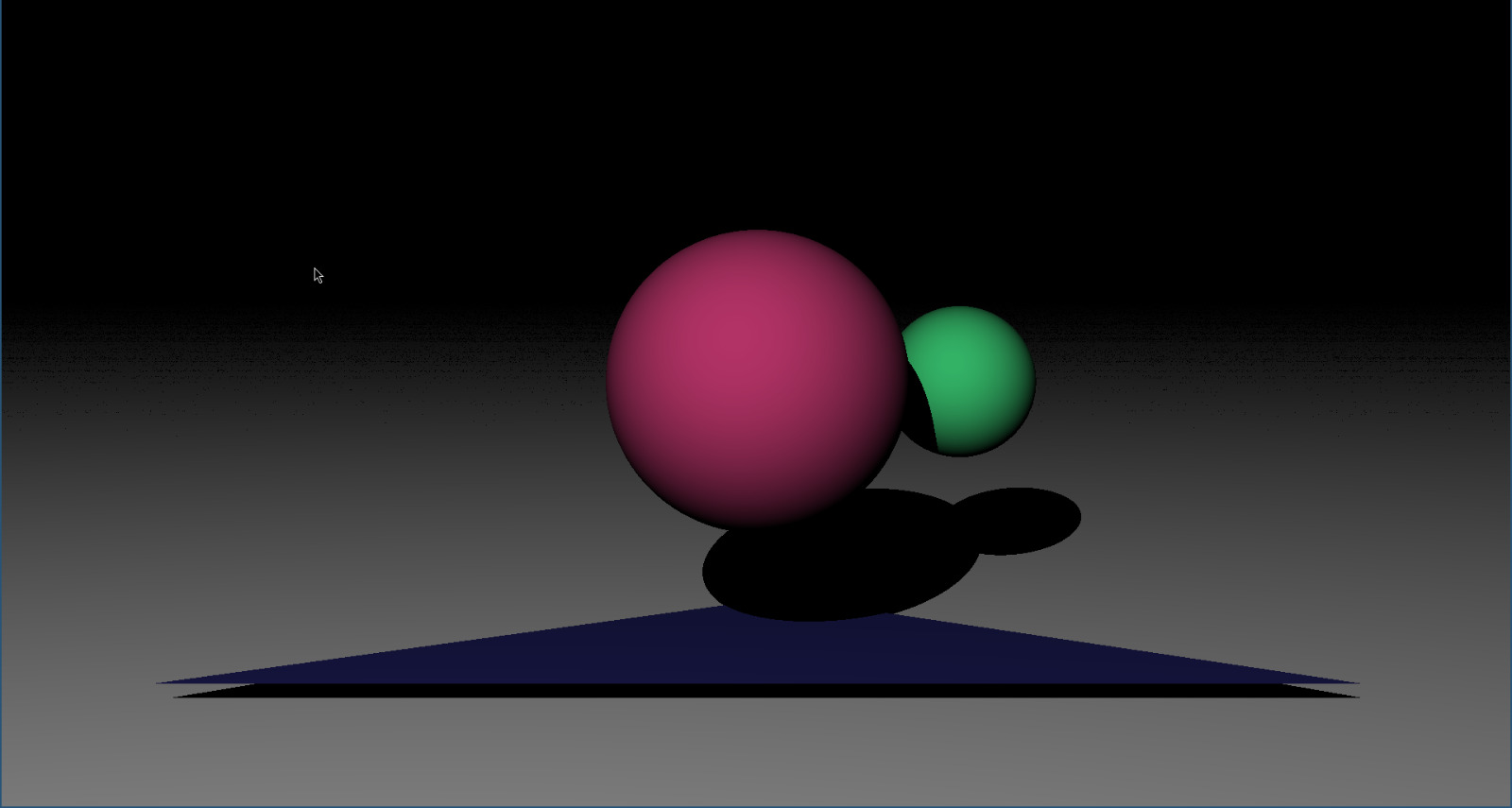

After basic shading, I started adding multiple objects. It's also at this point where implementing shadow rays made sense. They gives more perspective for where items are in the scene. Shadow rays originate from the intersection point towards the light to check for objects in the way of the light.

I encountered bugs here with which object was closest, modifying variables for the first hit vs the closet hit, shadow acne, among others. Setting the entire screen to green started to became my printf replacement.

Rendering triangles

The next object is usually an infinite plane. I implemented this one to gain confidence in intersecting different objects and have a floor for shading, but really it wasn't that much harder to write the function for triangle intersections directly. And 2 triangles totally suffice as a floor.

For ray-triangle intersection, I followed the Möller–Trumbore paper. It's surprisingly readable and helps with Phong shading later on. Scalar triple product simplifies Cramer's rule a lot in this case to help make the algorithm more efficient.

Reading objects

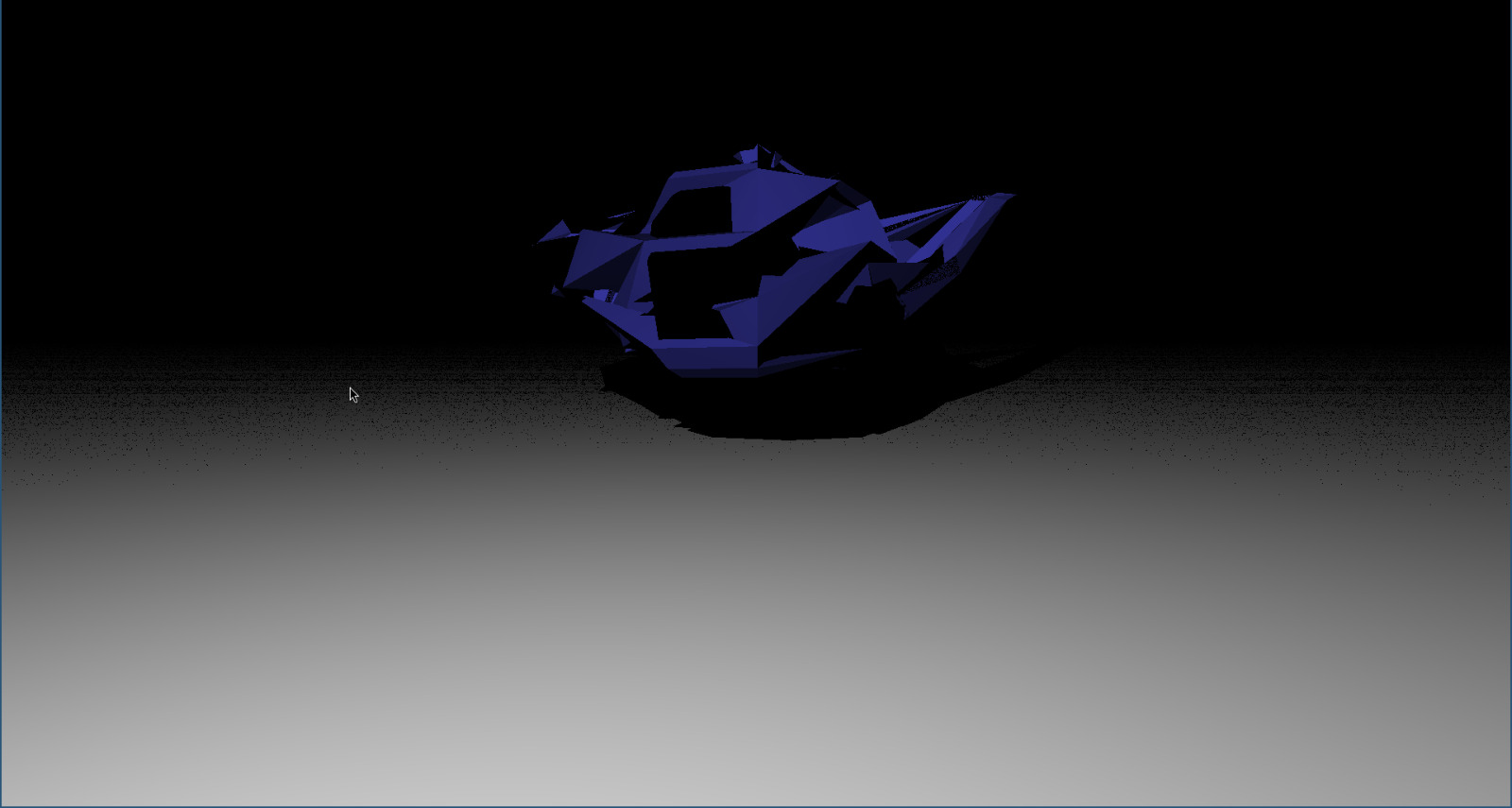

I wanted to render the classic Utah

teapot which is in an .obj file. The

parts I care about are in the lines that start with v, vn, and f. F (face) lines have indices (1 indexed) corresponding to the xyz positions defined on the v (vertex) or vn (vertex normal) lines. I ended up using sscanf as a very simple parser.

int result = sscanf(line, "v %f %f %f", &v1, &v2, &v3);A bug I got stuck on for a while is that vec3 arrays in OpenGL 4.6 using the std430 layout are aligned on 16 byte boundaries. I found it easiest to just define everything as vec4 and set the last item of vec4 equal to 0 when creating and referencing these storage buffers. Another bug I had was a classic off by one error given that arrays are 0-indexed and obj files are 1-indexed.

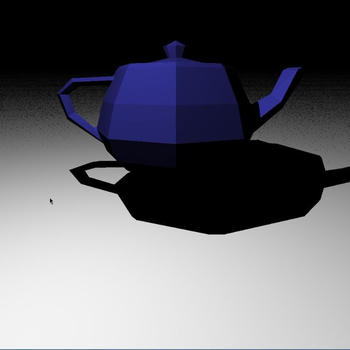

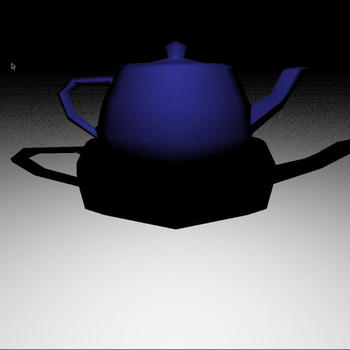

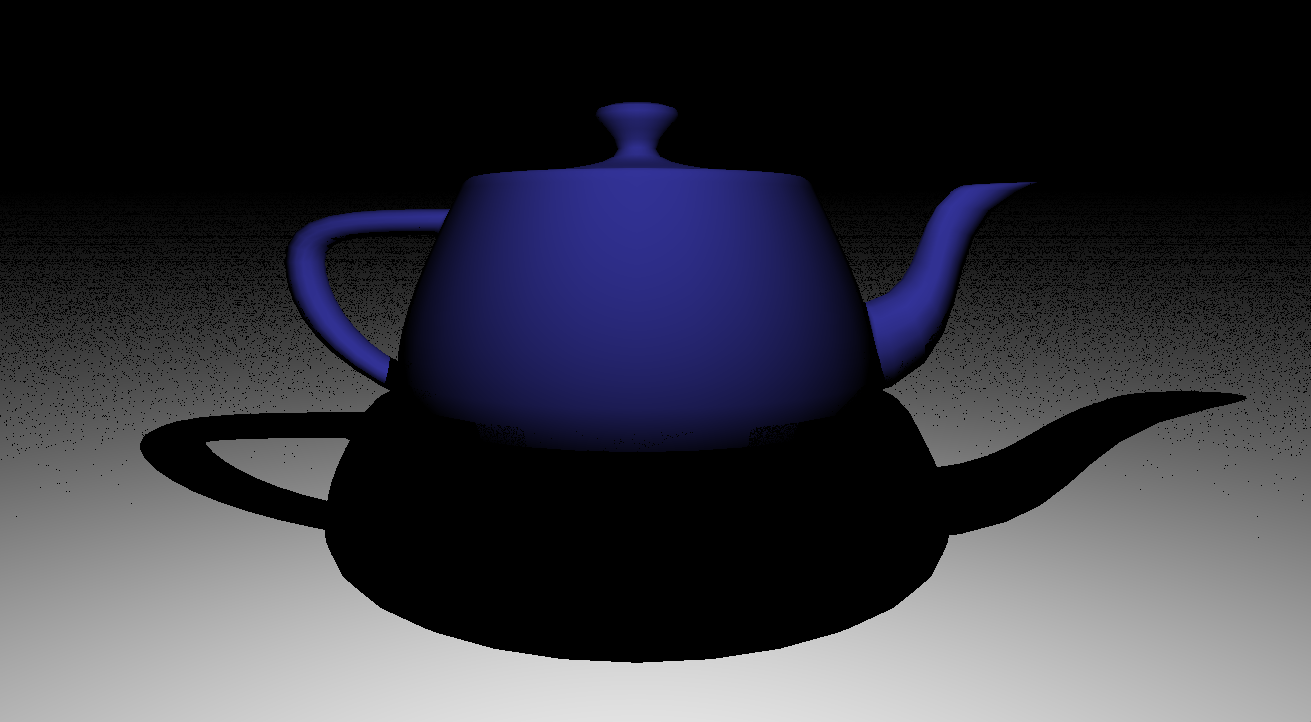

Phong shading

To better approximate a continuous smooth surface with finite triangles, I implemented Phong shading. Each vertex now has it's own normal. These are weighted using a convex combination of u, v, w from Möller–Trumbore intersection to find a better approximated normal for the point that intersects the plane. Both of the pictures below use about 500 triangles. One utilizes Phong shading while the other doesn't.

Conclusion

Writing a simple ray tracer was a surprising amount of fun. I was initially intimidated by a new type of debugging, thinking that I'd have to understand everything perfectly to debug it. Luckily, color based printf debugging worked well enough. There are many resources online that can make it simpler or harder depending on what you want. If you have a few spare weekends and haven't done computer graphics before, give it a shot!

Further implementation ideas

- Matrix transformations for each object

- Animation of object

- Animation of camera

- Benchmarking against CPU implementation

- Bounce light ray around the scene multiple times at random directions

- Add specular shading

- Implement more materials

- Speed up rendering large numbers of triangles

- Implement textures

- Implement more physically based rendering